Argentina 1 - Pizza

On our way to El Cuartito along the Avenida Corrientes, we passed a number of neon-lighted, vintage pizza spots that beckoned as I knew they would, prompting me to conclude that in Buenos Aires—as in New York—pizza matters a lot. I was hungry and psyched to reach our destination and so couldn’t stop myself from asking our hosts Walter and Alejandra, “Why aren’t we going to this one?” and “Why aren’t we going to that one?”

Of course, there was no answer—nor should there have been. It would turn out (and I knew this from the moment we arrived there) that El Cuartito was the perfect choice for my virgin Buenos Aires pizza experience.

The size of the crowd waiting outside and inside, the packed tables in two big dining rooms and the sea of pictures on the walls, the words, “Desde 1934,” painted above the pizza counter, the way everyone in the place applauded loudly at the sound of a shattering glass or plate: all of this stuff—and the pizza itself—led to my immediate realization that El Cuartito is a totally legit pizzeria. Imagine Katz’s Deli in New York if you can, but change English to Spanish, turn pastrami into pizza, and make most everyone Argentine—and voilà: El Cuartito. Thank you, Alejandra and Walter!

***

I should confess that of the many foods I had hoped to try during my family’s two week visit to Argentina last summer—and despite my knowledge that the massive Italian emigration that occurred in the decades around the turn of the 20th century included not only the United States, but also Argentina (and Brazil)—pizza was notat the top of my list.

Consider this a testament to the diverse array of other culinary highlights that were already on it. As such, my plans emphasized getting to the bottom of empanadas, experiencing a daylong backyard asado (barbecue), seeing whether the sandwiches de miga would be as good as they are at Dulce de Leche Bakery (a top-notch Argentine place in NJ that I have photographed for), learning about what Argentines eat at home, and becoming acquainted with Argentine dulce de leche (a milk caramel) in every possible way.

I did know, however, that a visit to Buenos Aires would be incomplete without a pizza experience. I had asked Walter and Alejandra if there were “Totonno’s-type places with coal burning ovens and fresh mozzarella.” They didn’t think so. I searched the internet but most of the info was in Spanish and my curiosity wasn’t intense enough to inspire deep digging. So I did what any person lucky enough to have friends to visit in a faraway place would do: I trusted my friends.

***

At far left, under the glass, are stacks of fainá, a chickpea flatbread that Argentines eat on top of their pizza.

I have read about the evolution of pizza in and around Naples, and how it crossed the Atlantic to the US where it was first eaten solely by the Italians but then was popularized and Americanized for mass appeal. I did not learn, while in Argentina, whether pizza had traveled a similar path to that country. But based upon the pizza that I had had there, I was curious.

I did a little research, looking at the points of departure for Italians who went to the United States versus those who went to Argentina. The results are from three sources — so the years don’t line up perfectly. But it seems that while most Italians who went to the US came from southern Italy (Port of Naples; later dates), a greater portion of those who chose Argentina came from the north (Port of Genoa; earlier dates).

Italy, though unified politically as one country, even today retains culinary diversity from region to region and town to town. It comes as no surprise that emigrants from Genoa might have brought to Argentina different culinary practices than those brought from Naples to the United States.

Consider fainá, a flatbread of chickpea flour that Argentines order by the slice and lay atop their pizza. Fainá, it turns out, is the Argentine version of Italian farinata, aka cecina, (or, in France, socca). All are versions of the same food that is eaten—topped with salt, pepper, and a drizzle of olive oil—as a snack along the Riviera coast in Italy and France. In Genoese dialect, it is actually called fainá.

(For “fainá” in New York, try the “socca pizza” at Pizza by Certé. Its gluten-free chickpea-based crust gets folded over like a crepe so that when you cut into it fresh mozzarella and sweet tomato sauce ooze out.)

Fugazetta with ham.

Two other Argentine pizzas that point to Genoa are fugazza and fugazetta, which happen to be the most frequently ordered combinations at El Cuartito (and, I imagine, throughout Argentina). Fugazza is a sauceless pizza topped with a mound of sautéed sweet onions; fugazetta is the same, but with a layer cheese under the onions.

The writer Daniel Neilson wrote on the blog, therealargentina.com, that fugazetta is “the classic Buenos Aires pizza” and that the Argentine government has even listed it as a food of “patrimonial value.” I don’t know what this means, but it sure makes fugazetta sound important. (I can attest. I saw many a waiter with fugazza and fugazetta pies flying past me at El Cuartito.)

“In 1893,” writes Neilson, “Don Augustin Banchero disembarked in Buenos Aires from Genoa and opened one of the country’s first pizzerias. The family [claims] to have invented the fugazza con queso...”

It’s clear to me that Banchero named fugazza after focaccia, a pizza-like flatbread with toppings that in Italy can vary by region. Did Banchero think he was making focaccia and not pizza? I doubt it. But perhaps, having come from Genoa, he based his fugazza pizza on an onion topped cheeseless focaccia of which he was fond. We won’t know.

(One of the dreamy vintage pizza spots we had passed on the way to El Cuartito was El Banchero.)

***

The plain "Mozzarella" pizza was my least favorite but it scored high on the comfort-food scale + it's perfect for kids.

I would be completely remiss if I didn’t devote a few sentences to the most significant feature of Argentine pizza: the cheese. Scroll through the slideshow via the top photo for views of El Cuartito and its pizza, and you’ll see that cheese forms a blanket on nearly every pie.

It may seem like cheese-overkill to those of us accustomed to a thinner layer or even a sparse dotting of cheese on pizza. And at 46 years old I know that I should not eat that much cheese too often. But there is a difference between mucho cheese in Argentina versus the US—and while it’s true that I ought to cuidado, the Argentine version is worth experiencing.

Piles of cheese in the US create a stretchy thick rubbery eating challenge, whereas in Argentina, it’s more of an ooze. That’s because the cheese on a “Mozzarella” pizza is only 75% mozzarella. The other 25% is cuartirolo, a soft melting cheese with roots in Northern Italy (Lombardy).

The net result is what I would call “comfort pizza.” Its warm and enveloping coat of stretchy cheese has a buttery top and crispy edges. My favorite turned out to be the spinach with bechamel and cheese. Really, as rich as pizza can get, I imagine. But I figured—and you should too—that if you’ve made it all the way to Argentina, which is near the bottom of the Earth, you ought to do it right. Pizza the Argentine way will have cheese. I suggest you embrace it.

*****

Notes:

1. People told me and I’ve seen written that most Italians came from southern Italy. I don’t know if it’s true — the numbers I discovered point to not true, but perhaps the Argentine population whose ancestors came from Southern Italy grew at a faster rate. What is certain is that there are definite food influences from the North that I don’t believe infiltrated the US with the same saturation.

2. There were four styles of pizza I had at El Cuartito. I’ve put them in the order of favorite to least favorite: 1.Spinach/bechamel/cheese; 2. Anchovies/sauce (no cheese); 3. Fugazetta; 4. Mozarella. I didn’t have Fugazza (onions without cheese) at El Cuartito, but I did have it at another pizzeria in Buenos Aires while I was there. And I must say, I prefer Fugazetta (with cheese).

--

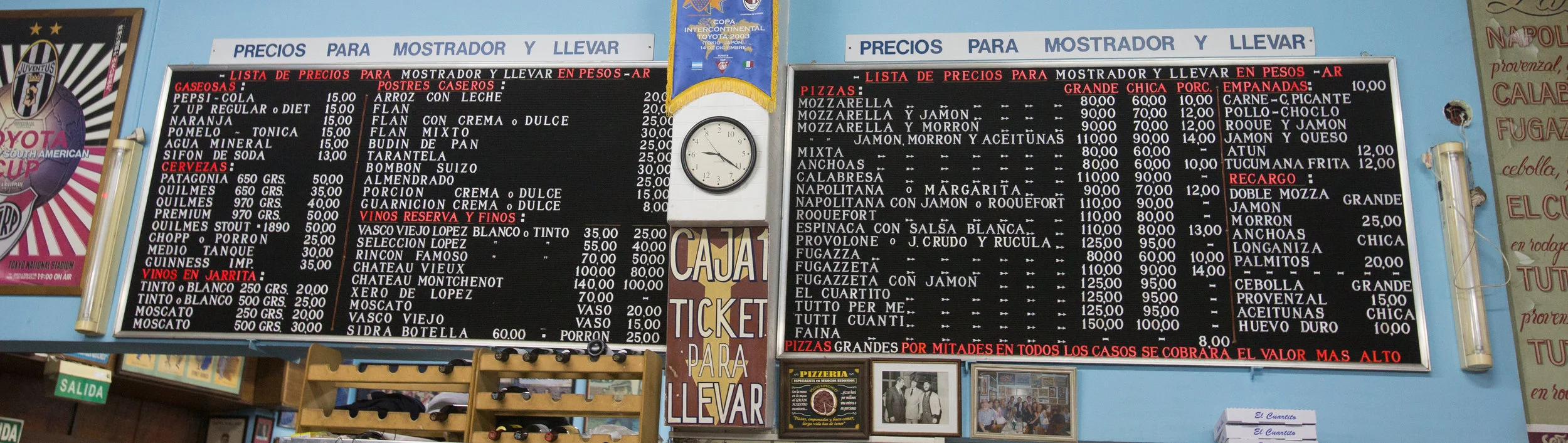

El Cuartito's menu, summer 2013. $ sign is symbol for Argentine Pesos. Exchange rate, when we were there, was about AR $5.5 per US $1 - but "black market" exchange rate was about AR $8.5 per US $1. At the "black market" rate, for instance, a large spinach and bechamel pizza was about US $13 (110÷8.5) [2017 Update: currency exchange rate is currently ~AR $16 per US $1.]

El Cuartito. Talcahuano 937, Buenos Aires, Argentina (El Centro). Tel. 4816-1758/4331. Map El Cuartito. Hours: Sunday - Friday 12 pm - 1 am; Saturday 12 pm - 2 am. El Cuartito's website.